What My PhD Is About (Condensed Version)

Dear Mom, Dad, and the rest of my relations: Please bookmark this page for future reference.

My field overall is known as History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. I am an historian of technology. In particular, I study technologies of illusion on the Victorian London stage.

What are technologies of illusion? Well, luckily, I’m not primarily a philosopher of technology, so I don’t (yet) have to answer that directly. But the term covers everything from the special effects technologies used onstage in dramatic performances (trap-doors, pyrotechnics, and electrical discharges, to name a few) to the technologies that transformed the theatre (for instance, gas and electric lights, scene painting, and fly galleries). It includes the technologies used by conjurors and mediums to accomplish their effects – smoke and mirrors, of course. And it includes the apparatus of scientific demonstrators who used spectacle in their work, like John Henry Pepper, famous for co-inventing* the “ghost” that bears his name.

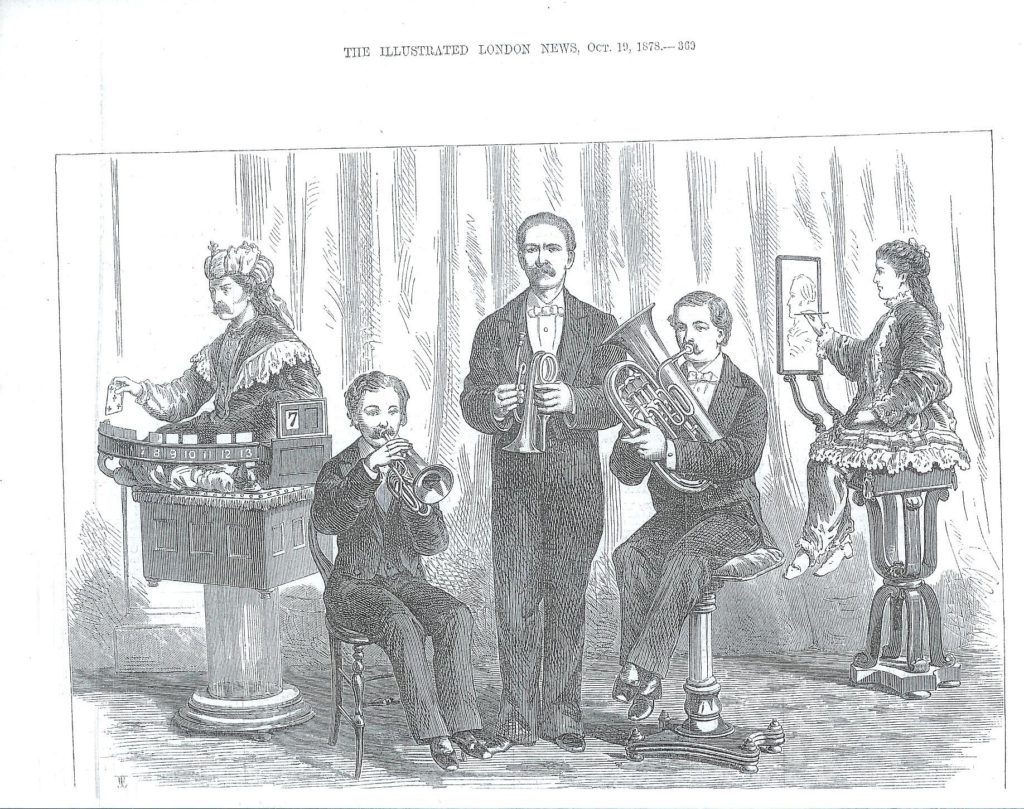

To give you an idea, my last major paper was on Psycho, J. N. Maskelyne’s card-playing automaton, first introduced in January of 1875. J. N. had a penchant for “automata”; in this image from the Illustrated London News, Psycho is the one on the far left, and J. N. is in the middle.

And to give you an even better idea: right now, for my upcoming specialist exams, I’m reading (among other things) Bernard Lightman’s books on the history of popular science in the Victorian era; Jim Steinmeyer’s and Milbourne Christopher’s histories of magic; Michael Booth’s and George Rowell’s histories of Victorian theatre; Philip Butterworth’s histories of special effects and pyrotechnics on the early English stage; and various histories of individual technologies such as clockwork, lighting, and precision mechanics.

This stuff is important because a) it’s really cool. I mean, c’mon. But also, because b) it illuminates some key issues in philosophy of technology, science, and representation.

First, it raises the question of what exactly is most important when identifying a piece of technology: what it does or what it is. Are two technologies the same if they have the exact same effect? Or can they still be different if they work via different mechanisms?

A little confusing, but here’s a real-life example: J. N. Maskelyne (again) once offered a reward to anyone who could duplicate an illusion of his in which he or his partner escaped from a box that had been locked, tied up, etc. Two young guys made their own box, copied his illusion, and demanded the money. But when J. N. examined the box (according to him), he found that its secret was different from his own. So he refused to pay, they took him to court, and the case ended with a hung jury. Eventually, the court awarded the two claimants their reward, since J. N. refused to show how his own box worked.

Now, J.N. went through the trial in part for the publicity, but the question he raises is a real one. When the purpose of a technology is to create a particular effect and to hide how it accomplishes that effect, is there any real difference between a technology that works, say, by clockwork and another that works by magic**?

Technologies of illusion (particularly, Victorian technologies of illusion) also raise the question of what exactly is the difference between demonstrating science and doing “magic”. Theatrical spectacle and popular science were both big in Victorian London, and they weren’t always easy to tell apart.

Conjurors used scientific discoveries (for instance, electromagnetism and chemical reactions) to accomplish their illusions, like the “science tricks” you often find today in popular science books and magazines for kids (for instance, the old Dr. Zed section of OWL magazine, or the Ontario Science Centre’s book Scienceworks), or like some beginners’ magic tricks (for instance, ones that use a Ph indicator to make a liquid change colour). Many also presented themselves as men of science, able to debunk mystics like Spiritualists and mediums – a tradition that many of today’s magicians, like Penn and Teller, Derren Brown, and James Randi, still follow.

Contrariwise, scientific presenters used optical illusions and spectacle to attract their audiences. Professor Pepper of the Royal Polytechnic, whom I mentioned above, was the most notorious of these. He presented phantasmagoric effects including transparent, moving ghosts that could interact with live actors; floating heads; a cabinet that could make people disappear; and instant on-stage transformations.

Are any of these people scientists? Is any of what they’re presenting genuine science? If so, why? If not, why not? Are they part of the scientific community? Or effective scientific educators? What were they trying to say science is?

Finally, the very nature of exhibition and theatre means that any investigation into technologies of illusion also raises issues of representation. It’s long been understood by theorists of the theatre that exactly replicating an object or phenomenon onstage isn’t always the most effective way to communicate its presence to the audience. For instance, (according to 19th-century theatre critic Percy Fitzgerald) if you want to present a fire in your play, there are better ways of doing it than actually lighting a fire onstage – not just because you don’t want to burn down the theatre, but also because, strangely, the audience finds some things that aren’t fire more firelike than fire itself.

Technologies of illusion have a twofold job to do: first, they have to actually accomplish whatever physical effect they’re supposed to accomplish, like send bolts of electricity between two swords in a duel or make a glowing skeleton levitate to the ceiling; but, second, they also have to do it in such a way that the audience is convinced by what they’re doing. It’s all very well to have the mechanism to make someone vanish, but even a genuine ingenious magic trick that no one can understand is underwhelming if presented poorly.

It’s like actors learn about stage combat: sure, it’s great to convince the audience you actually punched the guy your character is supposed to deck in the stomach, but the important part isn’t whether they perceive your fist actually connecting with his/her belly. The important part is your partner’s reaction. Even if you punch your fellow actor for real onstage***, if she or he doesn’t act like it hurts – just stands there like a robot – the audience isn’t going to read it as violence.

So technologies of illusion make interesting case studies because they highlight the difference between completing an action and representing the completion of that action. You need to understand both parts – how the technology physically worked (in the sense we use to talk about how a toaster or washing machine “works”) and how it psychologically worked (in the sense we use to talk about how the end of a story or an actor’s interpretation of a role “works”).

In other words, do I basically receive grants to research The Prestige? Yes. Yes, I do.

* Sort of.

** You’re probably thinking “yes” here, but before you settle on that answer, let me ask: when you say “yes”, are you thinking that the magic technology might be able to accomplish something different than the clockwork technology? Run smoothly under different circumstances or require different preparation or surmount obstacles the clockwork technology wouldn’t be able to? Because the point is that there’s no test you can do from the outside, short of taking the things apart and seeing how they work, that will differentiate between the two.

*** Not recommended.